Michi Weglyn had great stature in the history of twentieth century civil rights, yet she was a thin, small-framed woman whose self-effacing style masked her determination to bear witness against injustice. A West Coast farm girl, Weglyn was born in 1926 in Stockton, California to Tomojiro Nishiura and Hisao Yuwasa Nishiura. Recognized early as a promising young scholar, she attended Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts until personal misfortune forced her to withdraw.

Moving to New York City in the late 1940s to launch her career as a costume designer, she met Walter Weglyn, a Jewish refugee from the Netherlands, when both were living in Columbia University’s International House. They married in 1950. Walter was one of the few Jewish children from his hometown to survive the Nazi holocaust, so he well understood the importance of supporting Michi as she documented the history of her own internment in the 1940’s. He also was a tireless critic and editor, urging her always to tell the truth in her writing, even if the truth was not palatable or popular.

Before embarking on her career as a historian and writer, however, she overcame the prejudices of the post-war era to become a successful showbiz artist. She served as a costume designer for eight years on The Perry Como Show, a widely acclaimed music and entertainment television program in the 1950s. She also painted and wrote poetry while pursuing her demanding career in broadcast television.

When the Vietnam War and Watergate opened governmental actions to increasing scrutiny, however, Weglyn began to question the decisions that had led to her internment. “Curiosity led me into exhuming documents of this extraordinary chapter in our history . . .Persuaded that the enormity of a bygone injustice has been only partially perceived, I have taken upon myself the task of piecing together what might be called the ‘forgotten’ or ignored parts of the tapestry of those years.” Working without salary, she spent years reading through dusty boxes of documents at the National Archives, the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Library, and other institutions. No grant monies subsidized her extraordinary quest for the truth.

By the time Years of Infamy was published in 1976, piecemeal activities to redress the unjust wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans had already taken place. What the movement for redress still lacked, however, was a clear refutation of the claim, made by President Roosevelt and other military and civilian officials in 1941, that a “military necessity” had existed for the mass detention of Japanese Americans. Several wartime Supreme Court decisions, an official Pearl Harbor inquiry, and other governmental actions made the camps seem justifiable in the minds of Japanese Americans and many other Americans. As Weglyn herself said in the Preface to her book, “With profound remorse, I believed, as did numerous Japanese Americans, that somehow the stain of dishonor we collectively felt for the treachery of Pearl Harbor must be eradicated, however great the sacrifice, however little we were responsible for it . . .In an inexplicable spirit of atonement and with great sadness, we went with our parents to concentration camps.”

Finding the documents and writing a book that combined both scholarly rigor and moral authority were, as Weglyn soon found out, only the first two tasks involved in publishing her book. The next challenge was to find a publisher who believed in the book enough to buck the prevailing view that the camps were justified. Weglyn often told how the support of Howard Cady at William Morrow was instrumental in its original publication, while the support of new editors at the University of Washington Press helped to bring out a revised version of the book twenty years later.

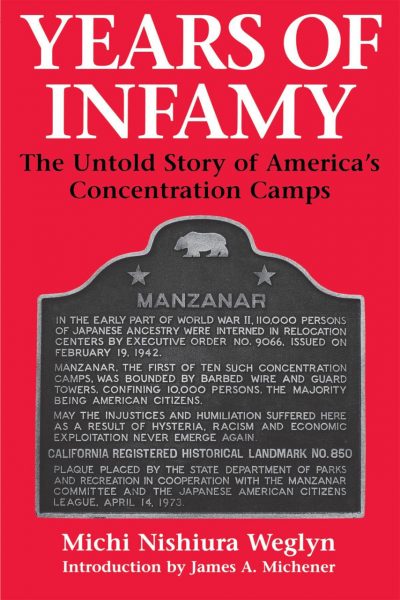

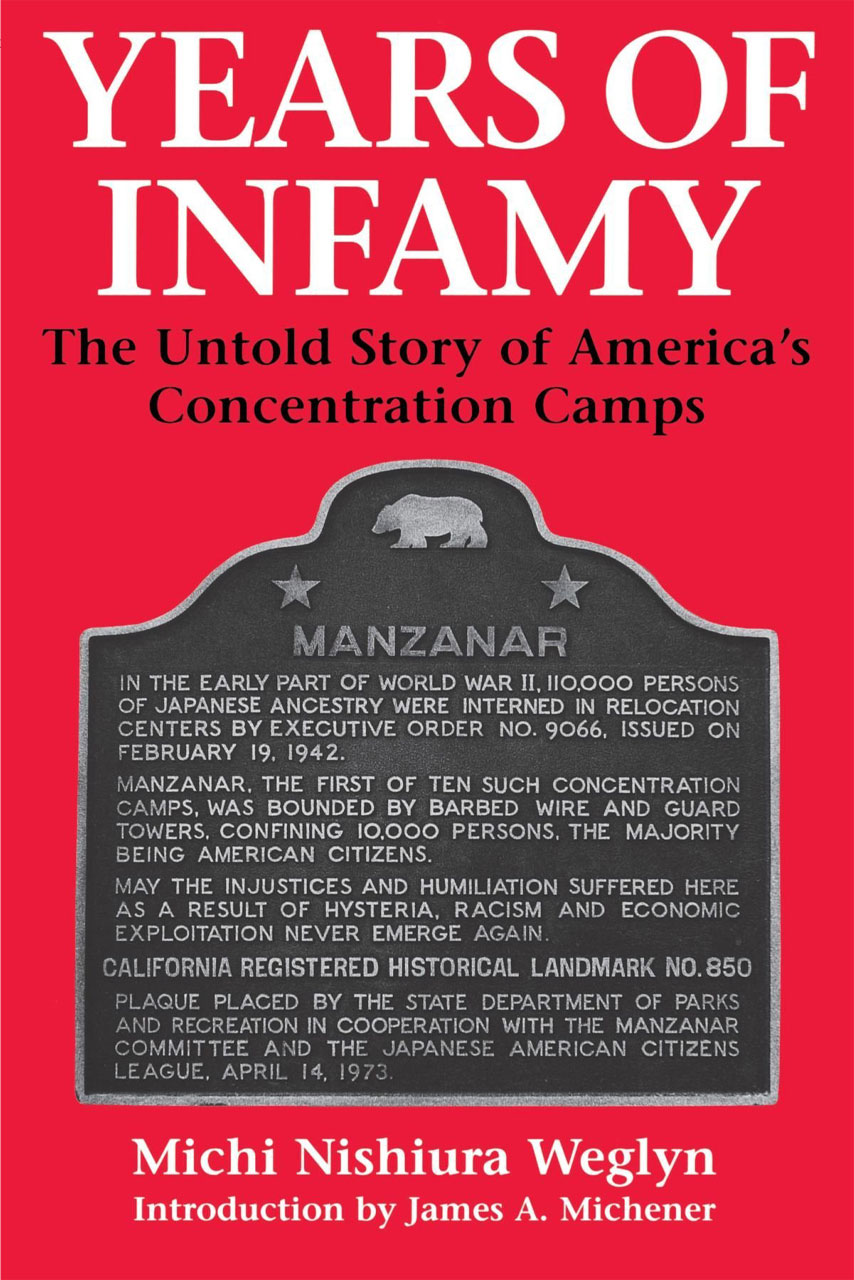

When it was released in 1976, Years of Infamy’s irrefutable analysis, supported by numerous photos, photocopies of government documents, notes, and references gave it immediate credibility. The power and eloquence of her writing also contributed to the awards and wide acclaim it received. Years of Infamy, whose title was a play on FDR’s comment that December 7th, 1941 was a “date that shall live in infamy,” was hailed by Japan scholar and former ambassador to Japan Edwin O. Reischauer as a “truly excellent and moving book . . .a terrible story of administrative callousness and bungling, untold damage to the human soul, confusion, and terror.”

Similarly, Kirkus Reviews called it a “formidable” work of scholarship and noted that it was, “Certainly the most thoroughly documented account of WWII Japanese American internment . . .Behind the claim of ‘military necessity’ Weglyn points to the U.S. desire for a ‘barter reserve’–i.e. hostages of war. Also discussed is the little known fact that Japanese nationals from . . .Latin American countries were exported to the U.S.” In this latter regard, Weglyn was 20 years ahead of her time, as the movement is just now gaining momentum to give redress to Japanese Latin Americans who were kidnapped early in World War II from Peru and other countries south of the border to barter for American G.I.s and American civilian internees.

The release of Years of Infamy in 1976 finally gave redress advocates the facts they needed to press their righteous claims in the courts and in Congress. The redress movement’s efforts led to a 1988 law giving $20,000 per former internee, and it was research done by Weglyn and other activist-scholars such as Aiko Yoshinaga-Herzig that made the difference for Congressional skeptics and critics.

Until her death on April 25, 1999, Weglyn served as a resource person for Japanese American railroad workers, Japanese Latin Americans, and anyone else who had been denied redress compensation for any reason. “She was a hero to so many people,” said Bob Suzuki, President of Cal Poly Pomona College and a longtime social justice advocate. “No matter how many honors she received, she always had the people who suffered inequities uppermost in her mind.”

Contributed by Phil Tajitsu Nash