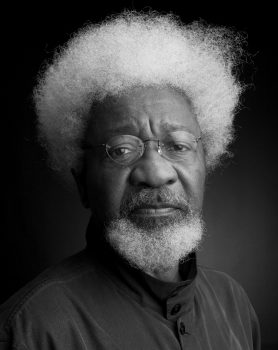

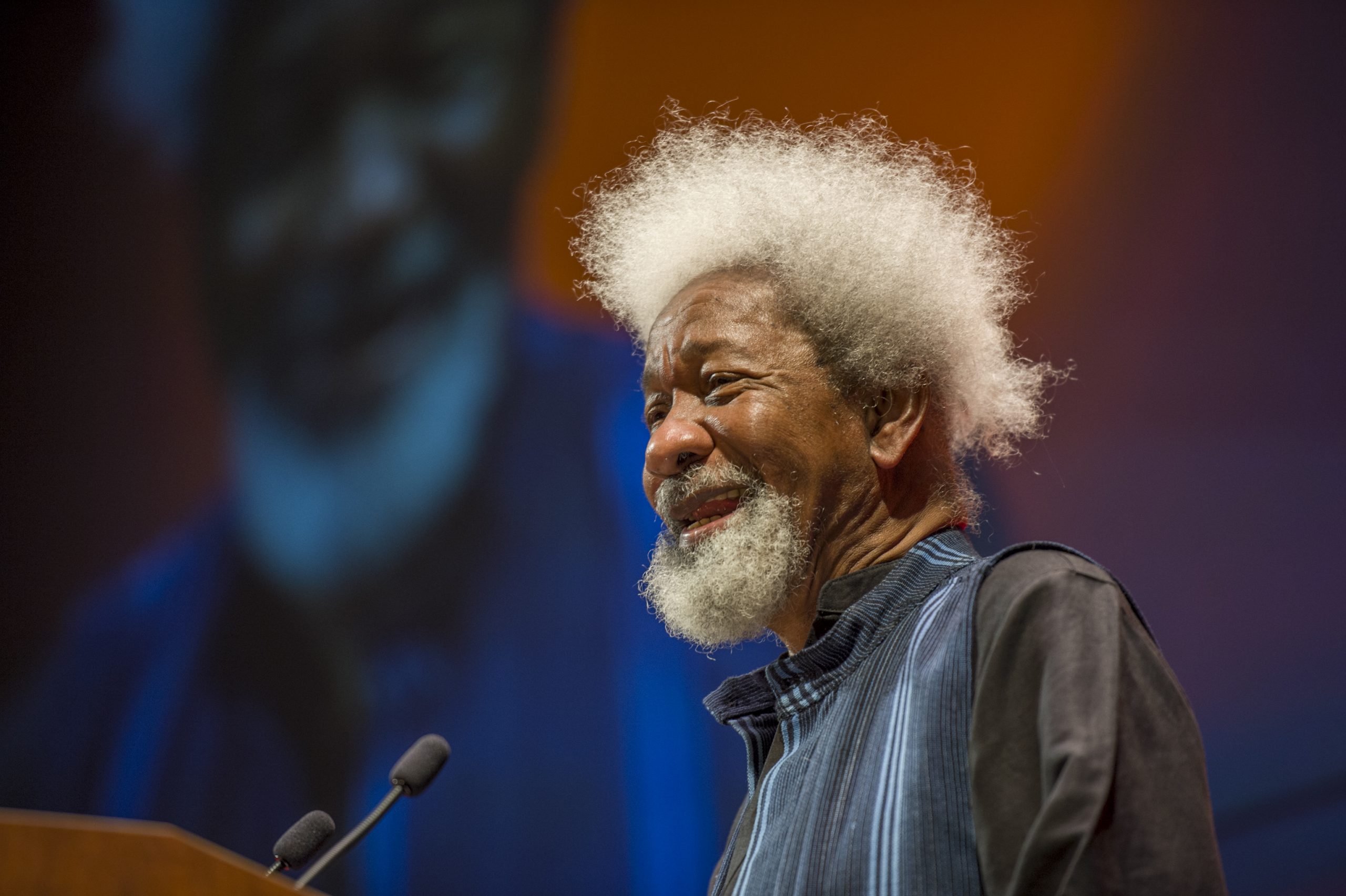

When awarding the prize, the Nobel committee described Soyinka, the creator of over 20 major works, as “one of the finest poetical playwrights that have written in English,” and also remarked that his writing was “full of life and urgency.” Soyinka (pronounced Sho-yin-ka) is the recipient of numerous other prestigious awards, including several honorary doctorates from universities all over the world. Apart from his stature as a pioneer in African drama written in English, Soyinka has produced a vast body of work—as poet, dramatist, theater director, novelist, essayist, autobiographer, political commentator, critic, and theorist of art and culture. Above all, he has remained a responsible citizen committed to the values of human freedom, truth, and justice. “Social commitment” he remarks, “is a citizen’s commitment and embraces equally the carpenter, the mason, the banker, the farmer, the customs officer, etc., not forgetting the critic. I accept a general citizen’s commitment which only happens to express itself through art and words.” From his earliest work to the present, spanning over 40 years, Soyinka has retained a remarkable consistency of vision in his dedication as an artist and as a socially responsible citizen.

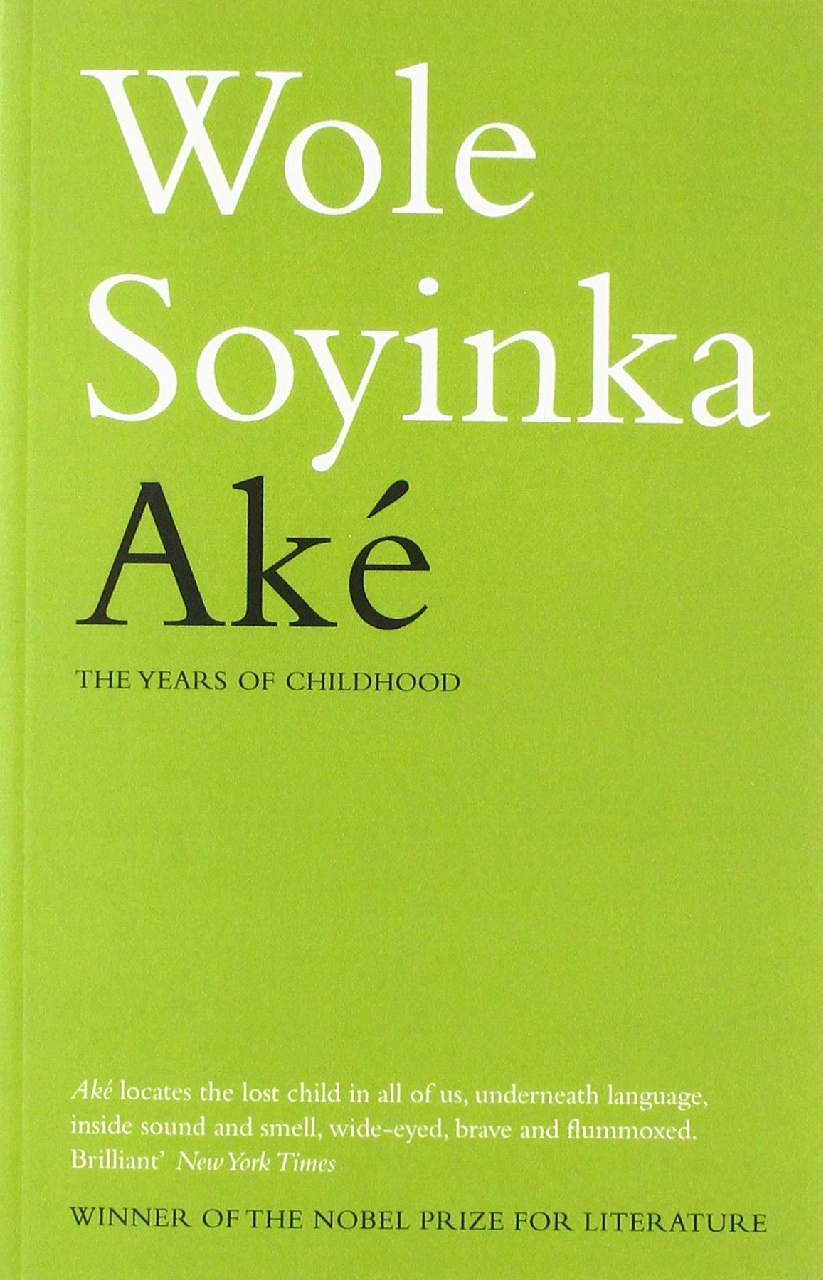

Soyinka’s vast creative talent is expressed in some 16 published plays—comedies, tragedies, and satires. His early play, A Dance of the Forests (1960), was written on the occasion of Nigeria’s independence, and includes his characteristic watchful irony and a warning not to romanticize the past as the Nigerian people and leaders forge a future for the new nation. Death and the King’s Horseman (1975) typifies his imaginative engagement with tradition. Priority Projects (1982) are satirical agitprop (literary propaganda) sketches, written and performed with the University of Ife Guerrilla Theatre Unit. His play, The Beatification of Area Boy: A Lagosian Kaleidoscope (1996), is about the survival of the underclass in a deteriorating urban landscape around Lagos. Soyinka has created dramatic and memorable characters including Elesin Oba, Iyaloja, Eman, Kongi, Sidi, Sadiku, as well as the autobiographically inspired figures of his mother (“The Wild Christian”) and his father (“Essay”) in Ake: The Years of Childhood (1981). He has published four volumes of poetry, the most recent entitled Mandela’s Earth and Other Poems (1988) with the striking opening lines, “Your logic frightens me, Mandela . . . Your bounty . . . that taut/Drumskin on your heart on which our millions/dance.” His three collections of essays include Myth, Literature and the African World (1976); Art, Dialogue and Outrage: Essays on Literature and Culture (1988); and most recently, The Open Sore of a Continent: A Personal Narrative of the Nigerian Crisis (1996). Soyinka has also written lyrics and musical compositions for a record album, Unlimited Liability Company, with songs such as “Ethike Revolution” and “I Love My Country” that are, like his newspaper articles, topical, hard-hitting, and responsive to particular situations.

An artist to the core—indeed, a cultural worker in the best tradition—Soyinka is deeply rooted in the African tradition of an artist who functions as the voice of vision of his times. He is not afraid to take action when necessary; he is never merely a commentator from the sidelines, and never untrue to the demands of his craft, whether his work is in the form of a poem, an essay, or a play. Indeed, in Soyinka we discover the remarkable fusing of the creative and the political; he invents new ways (often misunderstood by his critics) of linking the mythic and political; of forging imaginative links between harsh political realities and cosmological, spiritual realms.

Soyinka is a member of the Yoruba, one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, and he has strong roots in the Yoruba culture and worldview. Although his parents, Ayo and Eniola, had converted to Christianity, Soyinka himself never embraced the Christian religion; he feels more at home with traditional Yoruba religion and is a personal devotee of the Yoruba god Ogun (Ogum), who also figures prominently in his writings. Soyinka describes Ogun as “god of creativity, guardian of the road, god of metallic lore and artistry. Explorer, hunter, god of war…custodian of the sacred oath.” Changing historical times enable creative redefinitions of roles played by anthropomorphized deities like Ogun; today, Ogun, as god of metal and of the road, is worshipped not only by blacksmiths, but also by truck drivers and airline pilots—all workers in metal.

In addition to his Yoruba-Christian upbringing, Soyinka received a Western academic education. Born Akinwande Oluwole Soyinka near Abeokuta, Nigeria, Soyinka began his Western schooling in the Nigeria of the 1930s and 1940s, when it was still ruled by British colonizers. Next, he spent two years (1952-1954) at the newly established University College of Ibadan (now the University of Ibadan), where his classmates included Chinua Achebe, Christopher Okigbo, and John Pepper Clark, all of whom later made their mark in Nigerian literature. He then earned a B.A. degree from the University of Leeds (1954-1957) in Great Britain. He spent a year as play-reader at the Royal Court Theatre in London (1958-1959) and returned to Nigeria in 1960 on a Rockefeller Fellowship for the study of Nigerian traditions and culture.

Through his education, Soyinka imbibed the Western intellectual tradition, but in his writing he comes across first and foremost as a Yoruba, and it is from a base in Yoruba culture—his inspiration—that he responds to other literary and cultural traditions. His art is eclectic, a successful blend of African themes with Western forms and techniques. In his hands, African traditions assume meanings that are much wider than the ones accepted within their geographical location. “We must not think that traditionalism means raffia skirts,” Soyinka has remarked. “It’s no longer possible for a purist literature for the simple reason that even our most traditional literature has never been purist.”

Just as Soyinka confronts African “traditionalism” in the narrow sense, he also recognizes the irony of using the English language—a lingering legacy of colonialism. However, he is never apologetic about this matter; rather, he proudly accepts the challenge of making the English language “carry the weight,” as Achebe puts it, “of [his] African experience. But it will have to be a new English, still in full communion with its ancestral home, but altered to suit its new African surroundings . . . The price a world language must be prepared to pay is submission to many different kinds of use.” The role of English as a link language among people with various indigenous languages is certainly a historical reality in postcolonial societies. Language itself becomes a weapon for writers like Achebe, Soyinka, and others from the developing world to confront the disruptive remnants of colonialism and the negative continuities of neocolonialism in contemporary times.

Along with adapting the English language to his African experience, Soyinka optimally uses his education to transform literary forms from their European origins—often problematically considered universal—to suit his own cultural reality. In dramas such as The Road (1965) and Death and the King’s Horseman, Soyinka presents a new form: Yoruba tragedy that departs in significant ways from Western dramatic forms, such as Greek or Shakespearean tragedy. In this form, ritual, masquerade, dance, music, and mythopoeic language all work toward the very purpose of Yoruba tragedy, which is communal benefit.

Soyinka’s contribution to Nigerian drama has gone beyond his considerable achievement as a playwright to his key role in professionalizing the English-language theater in Nigeria, forming companies such as the 1960 Masks and the Orisun Theatre. The history of English-language professional theater in Nigeria is related integrally to Soyinka’s dramatic career. There is a clear correspondence between the timing of his plays and the prevalent political climate. Biting satirical plays such as The Trials of Brother Jero (1963), Opera Wonyosi (1981), Kongi’s Harvest (1965), and A Play of Giants: A Fantasia on the Aminian Theme (1984) indict African presidents-for-life (such as Idi Amin) as a “parade of monsters.” Most recently, The Beatification of Area Boy: A Lagosian Kaleidoscope (1996), theatrically enacts the survival of the urban underclass under Sani Abacha’s military regime.

Soyinka has the unique capacity not simply to write about social injustice in his creative work, but to meet the challenge and be an activist whenever necessary. There is no contradiction between Soyinka the artist, imaginatively exploring metaphysical matters in his creative work, and Soyinka the engaged citizen, commenting on Nigerian sociopolitical issues. He is concerned with the quality of public life and speaks openly as the conscience of his nation. (An example of Soyinka’s civic activism and his attempt to improve the safety of road travel in Nigeria was his establishment of the Oyo Road Safety Corps in 1980). His incarceration for nearly two years (although he was never formally charged or tried) during the Nigerian civil war (1967-1970) was a painful manifestation of his attempt to redress “the colossal moral failure” in the nation. “The man dies in all who keep silent in the face of tyranny,” he remarks in his prison notes, entitled The Man Died (1972). Soyinka considers “justice . . . the first condition of humanity” and recognizes that “books and all forms of writing have always been objects of terror to those who seek to suppress truth.”

Soyinka’s deep and energetic concern for his country has remained unflagging over the past 40 years of his literary career. He has always been a stern and uncompromising critic of social injustice, whoever the perpetrators might be. He roundly criticized Yakubu Gowon’s military government in The Man Died, just as he criticized Shehu Shagari’s “civilian” government in Priority Projects (1982) and Sani Abacha’s military rule in The Open Sore of a Continent.

Soyinka’s artistic vision, even as it engages with Nigeria, encompasses a universal scope. “A historic vision is of necessity universal,” he remarked in “The Writer in an African State,” a 1967 essay. In The Open Sore of a Continent, even as he explores the troubled notion of the nation in Nigeria, he makes links to similar crises of nationhood in Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union. He asks directly and poignantly, “what price a nation?” especially when atrocities are committed in the name of “national protection, sovereignty, [and] development.” His personal voice—bitter, angry, anguished—recognizes the traps of nationhood when the state acts as a repressive force crushing those who dissent. Soyinka’s criticism of Abacha’s brutal regime in the mid-1990s led to a close government scrutiny of all his activities. The government’s repression forced him into exile from 1994 until 1998, when democratic reforms began in Nigeria under General Abdulsalam Abubakar.

Like Ogun, god of the road, Soyinka’s creativity and courage blaze paths toward democratic ideals and social justice in Nigeria. “I have one abiding religion, human liberty,” he has remarked. With his passion for freedom, with his deep concern for the quality of human life, Soyinka’s work has profound significance in contemporary world literature.

Contributed By: Ketu Katrak