Faded fight posters on the walls at Cleveland’s Old Angle boxing gym served as an authentic backdrop for the poetry of Adrian Matejka, 2014 winner of an Anisfield-Wolf book award. Matejka’s 52-poem collection, “The Big Smoke,” centers on Jack Johnson, the first African-American heavyweight champion, who earned the crown in 1908.

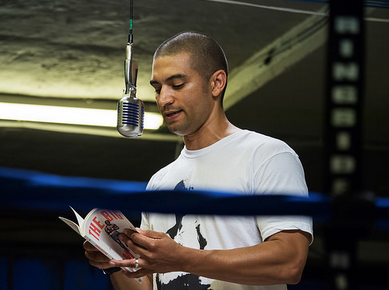

Gym owner Gary Horwitz rearranged his gym and his week to host. Dave Lucas, a founder of the “Brews & Prose” literary series, canceled his September plans and moved his audience from the Market Garden Brewery down W. 25th St. to the gym. The night featured Matejka’s reading, two live boxing demonstrations, and dollar bratwurst. Clad in a white T-shirt bearing Johnson’s likeness, Matejka, 42, took to the middle of the ring to read a selection of poems.

“Johnson was a folk hero, a contradictory figure,” Matejka said, testifying to the complexity of the boxer’s life. Born in Galveston, Texas in 1878 to former slaves, Johnson became one of the first African American celebrities. He flaunted an extravagant wardrobe and listened to Verdi’s arias while he trained.

“I didn’t mention that he had gold teeth, but he did,” Matejka added to his description later. “I didn’t mention that he used to change his clothes four to five times a day, but he did.”

Speaking to the crowd through an old-school boxing mic, Matejka began with the same poem that opens his book: “Battle Royale.” The title refers to a winner-takes-all fight in which black men were blindfolded and placed in a ring to fight for the amusement of white men. Last man standing won. Johnson got his start as a boxer in a battle royal in 1899. He won $1.50 for beating four other men and caught the eye of a local promoter. By 1910, he would headline in the “Fight of the Century” against heavyweight boxer Tommy Burns and see a $65,000 payday (today more than $1 million).

Johnson’s conspicuous glamour riled his white critics (and some black critics, as well — most notably activist Booker T. Washington). The physically imposing fighter – easily outweighing opponents by 40 pounds or more – took his lashes for being an unapologetically bold black man in the Jim Crow south.

As one of the most photographed figures of his day, Johnson had no shortage of press. Matejka used these references to create “Alias,” a sonnet composed entirely of callous monikers given to the boxer by mainstream newspapers like the Los Angeles Times:

The Big Smoke. Jack Johnson. Flash

nigger. The Big Cinder. Black animal.

Jack. Texas Watermelon Picaninny.

Mr. Johnsing. Colored man with cash.

His rendering of Johnson made the sport of boxing more accessible to some of those in the audience. “There’s something extra besides the brutality,” one woman told Matejka during the question-and-answer period.

In the midst of the demonstration bout that followed Matejka’s reading, boxer Darryl Smith received a gash near his eye. A little pressure from a towel, a dab of Vaseline — and the fight went on. Time for round two.