by Kathleen Cerveny

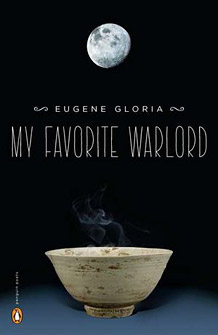

My Favorite Warlord, by Eugene Gloria, is the recipient of the 2013 Anisfield Wolf Book Award for Poetry. This award, administered by the Cleveland Foundation, recognizes books that have made important contributions to our understanding of racism and our appreciation of the rich diversity of human cultures. Now in its 78th year, the Award is juried independently by a panel of scholars led by Dr. Henry Louis Gates.

In this, his third book of poetry, Eugene Gloria continues his focus on his cultural origins in the Philippines. He offers poems that range between accessibility and a satisfyingly complex look at the experiences of Asians growing up in America; he examines family and home — both here and far away — and identity and belonging. From his time growing up in San Francisco and Detroit, Gloria places these issues in the context of an America familiar to us all. At the same time, he invites us to learn something of Asian culture through the use of poetic idioms and historic references that often require thought and close reading.

The book’s many-layered but quite approachable title poem is an example of this. It references Kurt Cobain, the elegance of the zen garden, and historic figures from ancient Japan and 20th century Portugal, in describing the poet’s difficult relationship with his father; “an irascible manager” whose presence pervades the book.

The poem’s opening epigram; “Hello, hello, hello …” from the grunge band, Nirvana’s iconic song, “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” suggests this will be a poem of alienation. Indeed, not three lines in, Gloria’s narrator says “hello” silently to his father watering the flowers in his garden, as he drives past his aging parent’s home — without stopping. In 24 short lines, Gloria gives us a deeply layered, cross-cultural and completely real portrait of the difficult relationship between a father, who cannot change the dominating legacy of his cultural heritage, and a son who has taken another path.

Indeed, as the title poem suggests, the relationship with the father is a central theme in the book. A group of six poems, “Photographs With Images of My Father,” sensitively explores aspects of the father’s life and personality through the use of different poetic forms.

Throughout the book, Gloria mixes free verse with ancient poetic forms from Asia – haibun and pantoums. There are elegies, allegories, and psalms, references to the eastern religions of his cultural heritage and the Catholicism of his own upbringing. Although some readers may need Google on hand to understand all the references, it is an effort worth making.

Indeed, one poem, “Cogon,” a haibun, still has me wondering. Cogon is a tall, coarse grass used by villagers of the tropics to thatch roofs. Cogon Shrine is a Catholic church in Manila. Both of these may, in some way, relate to the poet’s Philippine heritage. However, how the title relates to the prose section of the haibun about men lost to the seduction of the “daughter of the mountain” eludes me, even after research.

My Favorite Warlord is a journey in memory, progressing in time through the four sections of the book. Although not titled, one might name them; Assimilation, Awareness, Identity and The Poet Confronts His Gift. These are rich, poignant expressions of the challenges of an Asian family’s efforts to fit into American society. From “Here, On Earth”

Here, on earth we are curtained by rain.

A subset in the far corners floating

toward the center. We are an island

in landlocked America. We are

Thai, Filipino, and Vietnamese.

We are, all of us, post exotics. (34-39)

and from “Monsoon Season”:

… I was seven that monsoon season

before the highway had a proper name

before my father became a U.S. citizen

and shortened his name to Sid. (6-9)

Gloria’s poems explore the exhilaration and danger of freedom in America’s “summer of love” and confront us with the prejudice and brutality that continues to this time, by those considered ‘other.’ We find tender personal stories of family set against the horrors of war, the burning of monks and astronauts. There is the near rape of a sister, the ‘honor killing’ of a young girl by her brothers, the 1982 murder of Vincent Chin, a Chinese man beaten to death in Detroit by two American auto workers angered by Japan’s impact on the auto industry.

In the final section of the book, Gloria, like many poets before him, questions his own gifts. From “Trees As Soldiers March:”

There are other circles of hell reserved

For other margin-huggers like me

Despite all those statues weeping blood,

Praying their thousand, thousand mighty prayers.

The beauty of my god is allowing me to suffer

While I invoke his name daily through the small

Disasters I make with my own hands. (20-26)

These final poems, in a way bring us back to Cobain who, in “Smells Like Teen Spirit” states:

I’m worst at what I do best

And for this gift I feel blessed.

Eugene Gloria’s gift is to bring us elegiac and sensitive encounters with the cultural experience of the growing number of Asian ‘others’ in our increasingly multi-cultural America.

Kathleen Cerveny has been a working artist, educator, development officer, and award-winning producer of arts programming for Cleveland Public Radio. She is also the Cleveland Foundation’s director of arts initiatives where, for two decades she has directed its arts and culture programs and led major initiatives in public policy and organizational advancement for the arts.

Kathleen Cerveny has been a working artist, educator, development officer, and award-winning producer of arts programming for Cleveland Public Radio. She is also the Cleveland Foundation’s director of arts initiatives where, for two decades she has directed its arts and culture programs and led major initiatives in public policy and organizational advancement for the arts.

Kathleen is completing a Master’s degree in poetry through the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Creative Writing Program. She is a published poet and held the title of Cleveland’s Haiku Champion from 2009-2011 and currently (2013-14) is the Poet Laureate of the City of Cleveland Heights.